Good news / bad news time. The good news is, I finally made a start on diagramming my system. The bad news is, it looks like this:

I drew this diagram about a week ago, when I was stuck thinking about what to do next. I'm going to call diagrams like this pragmatic diagrams, because they are imaginative, personal, and non-rigorous tools for exploring problems too complex to keep in mind at one time. It is a standard practice in software organizations to use diagrams like this collaboratively as well as on one's own. Almost every design meeting reaches a point where someone needs to pick up a marker and draw some kind of picture on a whiteboard of the system under discussion. In these meetings, the diagram helps the group coalesce around a shared model of the system. A significant amount of time may be spent on critiquing the way the system is drawn, because a software-writer's way of portraying a system is actively understood to refect some or all of:

- The way that the writer is comfortable thinking about it[1]

- Some goal the writer has for the system (i.e. the portrayal visually suggests that an intended change or addition makes sense)

- Concepts or relationships that the writer intends for the audience to understand as more important than they may otherwise appear

- The view of a system from the perspective of a particular domain (e.g. the security characteristics of the system)

At the end of a meeting that produces a diagram like this, one of the participants usually takes a picture of the diagram and says the traditional prayer to the fickle gods of documentation: "I'll put that on the wiki."

Whether or not the thing actually makes it to the wiki, and if so, whether it's ever referenced again, is no one's primary concern. The goal of the diagram is not to convey information the way a letter conveys information. Instead , it's a mnemonic device that helps participants in the conversation maintain a shared context over a period of days, weeks, or months while they are working collaboratively on a system. If a system is familiar enough to everyone involved in building it (e.g. it is comparable to other systems they have built or understood) the diagram may function simply to validate their shared understanding, after which it is disposable, because it's not required for collaboration. If a new person joins the collaboration, they may be shown any relevant diagrams by one of the people who was at the meeting--in this case, the diagram serves as a compressed version of the original conversation, which the OP walks through for the benefit of the new member[2].

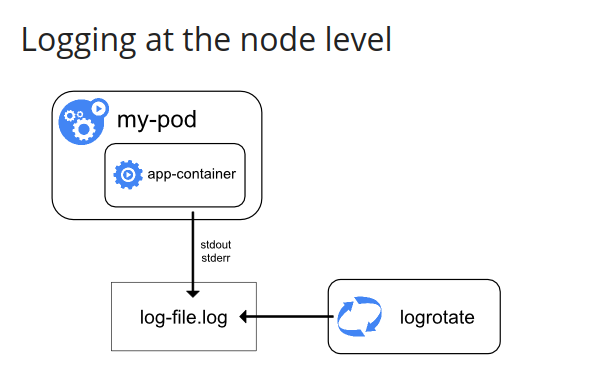

There's another kind of software diagram that's also very common: I'm going to call it the external-facing diagram. The following, taken from the documentation of a popular platform, is a perfect example:

Externally-facing diagrams are explicitly meant to convey information to an outsider--someone who wasn't in the room when the diagram was made. The diagram is usually aimed at comprehension by a user with a specific purpose--the diagram above is in documentation, so the intended audience is someone trying to understand / use the system. Another common use of external-facing diagrams is in tasks like security review or sales--a diagram will be part of what a system designer provides a customer, regulator or security reviewer to help them evaluate the system. In these cases, it would be naive to ignore the author's incentive for the reader to interprest the diagram a certain way[3]. External-facing diagrams are usually made at the end of software lifecycle stages--when showing a system to outsiders in its final form[4]. This type of diagram is often not very useful to software-writers actually working on the system, and tends to drift out of date as soon as it ceases to be useful for motivating a decision.

Neither of these types of diagrams are well-suited to the task of collaboratively building systems within large communities. The manipulability of pragmatic diagrams--the ability for other meeting participants to step in with their own markers, to expand, challenge, or clarify--comes at the cost of legibility. The diagram that comes out of the process doesn't contain the information it represents, but rather refers to the shared context from which it emerged, and which it helps recall. The much stronger relationship between external-facing diagrams and the information they encode comes at the cost of collaboration--it is rare that such a diagram affords the actual possibility of amending the system--and sometimes even practical applicability, in cases where the diagram presents a view so abstract that it's not useful for addressing the system as it actually exists.

The common solution to this problem--the problem of collaborative building on a planetary scale--prioritizes the creation of shared contexts above neat visual representation. To see how this works, we will imagine fitting a building with an HVAC system. The group that builds the system, broadly construed, includes everyone from iron miners to web developers--it includes everyone necessary to the process of extracting chemicals from the earth, turning them into HVAC components, designing a system from them, installing them, and using them. In this distributed collaboration, each domain--mining, manufacturing, HVAC system theory--constructs within itself a vocabulary of terms with agreed relationships. Because system designers need specific information to compare one air-handler against another, that information is unfailingly provided by air-handler manufacturers, and, ideally, social forces create an incentive for it to be accurate[5]. When it works, this process facilitates coordination across domain boundaries. Someone whose work is in a specific domain is able to pick up the context of the adjacent domains[6] and expect that it will be legible--that it will reflect a view of reality that is consistent with her "home" domain even if it is too detailed, abstract, or incongruous to be of use generally. For instance, an HVAC system designer can build fluency in the context of HVAC installers, to better understand why some designs succeed and others don't.

But there isn't an identifiable type of diagram that facilitates this process--such a diagrammatic method would require mediating between the vocabulary of each domain, which is hard and dubiously useful[7]. Instead, practitioners accept that, while there may be a conceptual gradient between "iron ore in the ground" and "cold air coming out of a vent," in practice it's easier if we split that gradient into domains[8] and accept some arbitrariness in the exact locations where the vocabulary of one domain gives way to that of another.

You might accuse me of digression here. These are clearly separate topics--the concept of pragmatic vs external diagrams is about how one system can be described in different ways, while the concept of a task-gradient broken into domains considers an interdependent set of systems. But I think my software-writer comrades can probably already guess how this song goes: software is both. When we take a holistic view of "a website," we might be talking about it as "the thing that would look totally different described by a compliance officer vs by its maintainer" or we might be talking about "The domain within software development adjacent on one side to back-end and infrastructure, and on the other side to UX[9]" And if you notice that every domain in the software gradient--circuit design, firmware, operating systems, userland, network, services-- has its own pairing of pragmatic and external diagrams, you see an interesting thing. At each layer, the diagrams that are available and legible to non-practitioners are the external-facing diagrams--which practitioners rarely use themselves, and may not even recognize. Across the entire software-production gradient, from silicon to CSS, there is a pragmatic practitioner oral tradition and there is an outward-facing set of symbolic "official"[10] representations. The practitioner oral tradition must preserve the adjacencies of the task gradient to be useful. This is what holds it accountable to reality--I can wander over to the desk of the person in an adjacent domain and ask them what they meant by something. But the external-facing representations have no incentive to form a continuous gradient, since the activities that those representations are meant to enable--selling, gaining approval, legislating--do not cause them to form a gradient relative to each other.

As I begin to document my system, I'm going to be trying out some ways of publishing explicitly the practitioner oral tradition--the pragmatic[11] understanding of the layers of the system as a task gradient. This will mean setting some domain boundaries, choosing a vocabulary for each domain, and demonstrating how the vocabulary defines and captures the important concepts within the domain. This can be a collaborative process--I'd be grateful for feedback when I inevitably make mistakes or do a good job. Hopefully, this will help to facilitate productive conversations about how to build systems.

One of the pitfalls of teams with highly skilled, authoritarian, or charismatic leaders is unthinking acceptance of the leader's preferred vocabulary, notation, or context for understanding the system. Even when not malicious, this can cause big problems. ↩︎

I'm intentionally omitting commentary on power dynamics from the main text. That's not because those dynamics are absent in practice; rather, it's because I want to cover the idealized version before complicating it. I would argue that this approach is not inherently flawed--given a group with strong norms of respect, it's an efficient and useful way to do things. ↩︎

e.g. as attractive, or secure, or clear, or simple. ↩︎

For instance, people with different jobs often use wildly different vocabularies. It's fairly common for a diagram drawn by a software-writer, based on a software-writers intuition about how to think about a system, might later be heavily edited by a compliance officer, whose natural vocabulary is that of regulatory constraints. This is often a back-and-forth process of communication between those involved, but they are not collaborating on the system; they are collaborating, without changing the system, on a mutually-acceptable representation of it. ↩︎

again, idealized. ↩︎

I think of "adjacency" in terms of input / output. You are adjacent on one side to the domain from which you get materials, and on the other side to the domain that uses what you produce. ↩︎

The vocabulary of a domain evolves because it is useful in the domain. By definition, adjacent domains care about different things, leading them naturally to different vocabularies. Any negotiated correspondence between those vocabularies has to absorb both their incongruities and their tendency to continue to change independently over time. ↩︎

for this, read, from Melville, "What then remains? nothing but to take hold of the whales bodily, in their entire liberal volume, and boldly sort them that way." ↩︎

Ask five different software writers to pick the correct adjacencies, get six answers. ↩︎

"official" meaning "claimed publicly to regulators, customers, etc." ↩︎

I'm only just remembering that "pragmatic programming" is already a buzzword. This is not that concept. ↩︎