Today we're going to buy a domain name[1]. It's not especially exciting or complicated,

but it's important and unfamiliar to most people, so it deserves its own instructions.

We're going to buy it from AWS, using our existing AWS account. At the time I'm writing this,

.com and .org domains cost $12 per year, .net domains cost $11 per year, and other top-level domains

(the technical term for the .com or .net part of the domain name) cost other amounts,

some of them quite high[2]. I checked a few different popular domain name vendors, and the prices

through AWS are pretty representative[3].

This costs money, so I want to be extra clear about what's happening:

- We're going to reserve a domain name. If you use one of the TLDs I noted above, you'll pay about $12 to reserve the domain for one year; this will autorenew by default, charging you $12 per year.

- We're going to set up a hosted zone, which is the actual networking plumbing that lets us point our domain at our website. This costs an additional $0.50 / month.

- We're not going to set up a website in this exercise--that's going to come later, because I can't fit that whole process into this post. If you'd rather wait to reserve your domain name until I publish those later instructions, that's fine, but note that domains can take up to 3 days to be usable from the time you register them (it's likely they'll actually take less than a day, but YMMV).

At the end of this process, we'll have a domain and a hosted zone, which together will cost around $18 / year ($12 / year for the domain; $0.50 / month for the zone). All clear? Let's get started.

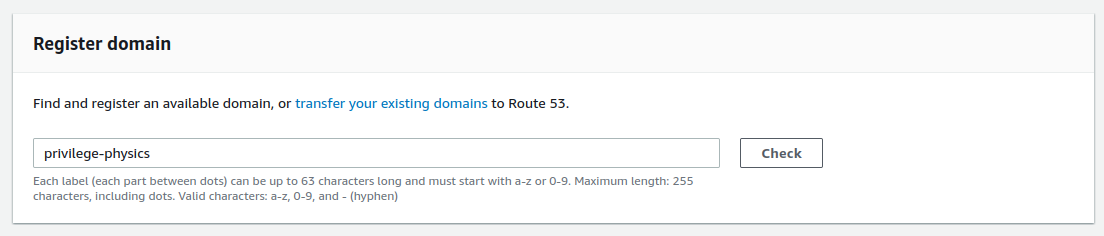

We're going to use the AWS UI, instead of terraform, to set this up. Sign in to your AWS account and go to the

route53 console[4]. You should see a big "Register Domain"

panel in the middle of the screen. Enter the domain name you want and click "Check." If you're having a tough time picking

a name, consider using a random word generator. You can use hyphens (-) in domain

names, and I usually find that there's a two-word pair that I like. It can be nice to have a domain that's memorable but

not super-specific, so that if the way you want to use it changes, it doesn't look out of place.

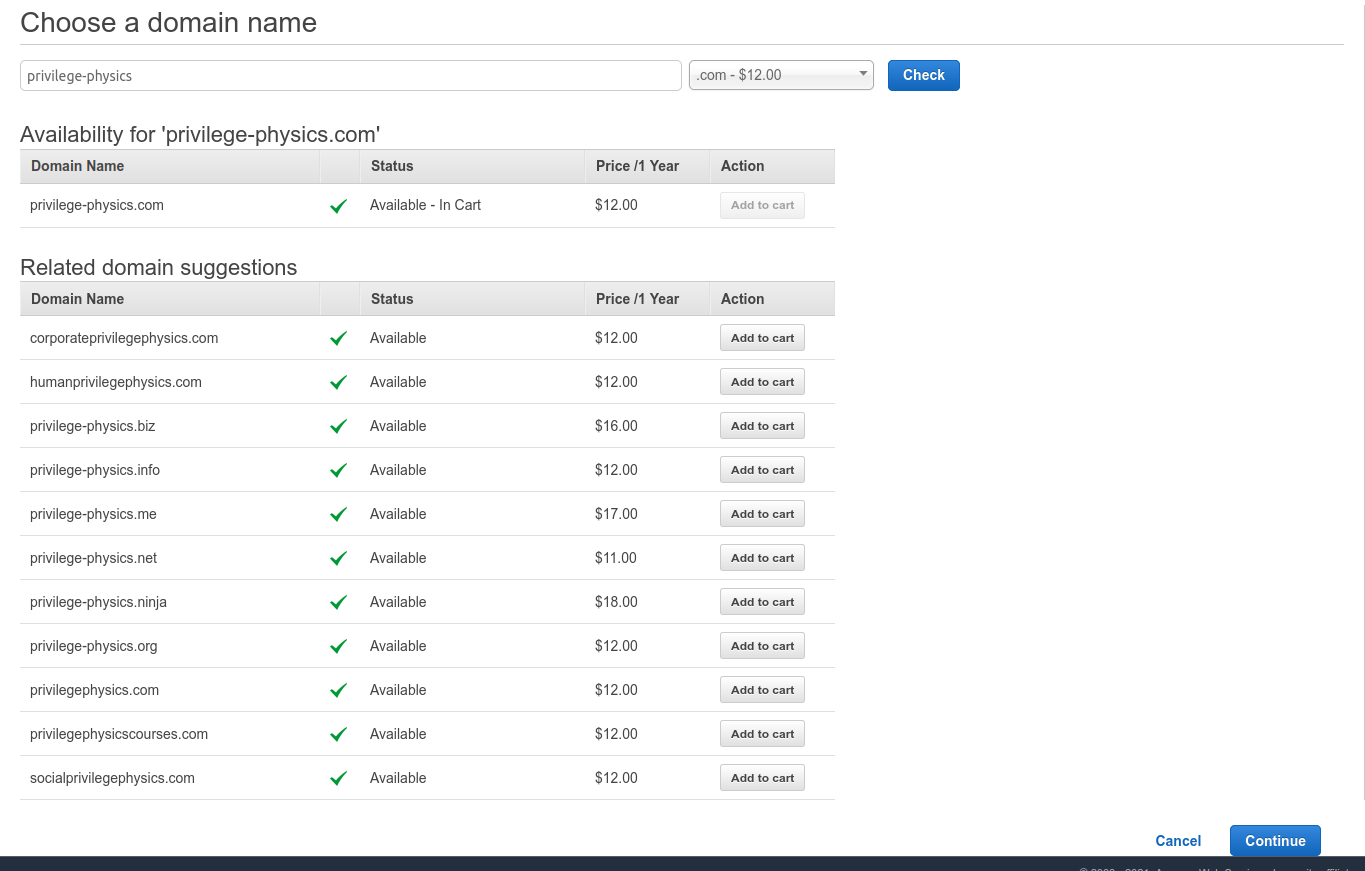

On the next page, if your domain name is available, you should see a dropdown list of TLDs to choose from, with prices. If the domain name you want isn't available at the TLD you want, I'd advise choosing a different domain name and searching again until you find one that is. When you've found an available domain, click the blue "Continue" button on the bottom of the screen.

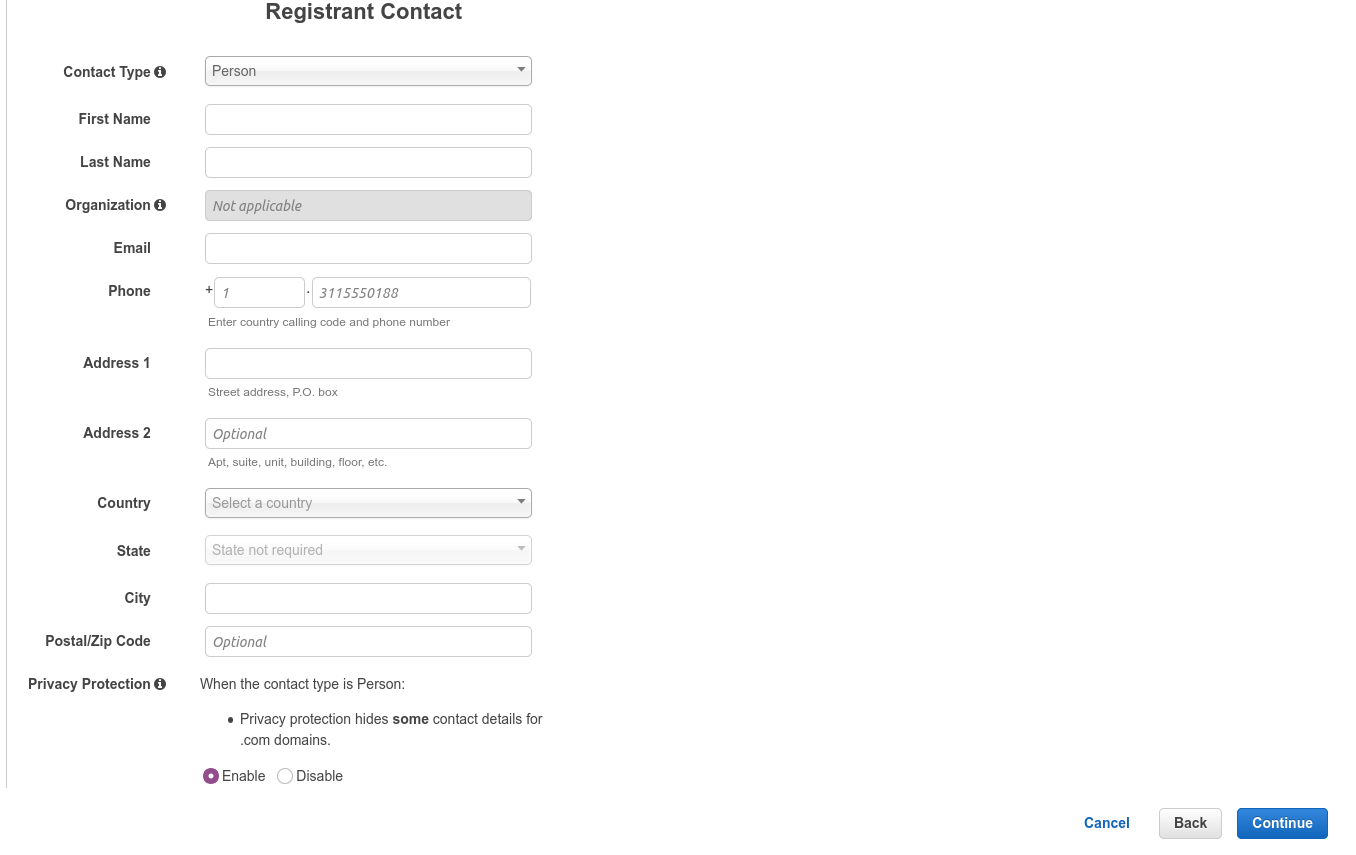

On the next page, you're asked to fill out the contact information for the domain record. Every registrar needs

to maintain this contact information for all the domains it issues. The rules for how this information is handled vary

based on the TLD. For some TLDs, like .us domains, the rules explicitly say that the domain owner contact information

must be public--that is, anyone can look up the contact information for whoever owns a .us domain[5].

If you are registering a domain as an individual (rather than as a company or some other type of organization) AWS

provides free domain privacy for most TLDs. To use this, make sure

that the "Contact Type" field at the top of the form is set to "Person" and the "Privacy Protection" setting at the bottom

of the form is set to "enable." To see what information is published for domains with privacy protection enabled,

you can look up this site (raphaelluckom.com ) on the ICANN whois lookup site. In my opinion,

it's pretty sensible and privacy-preserving. Enter your contact information in the form and click "Continue".

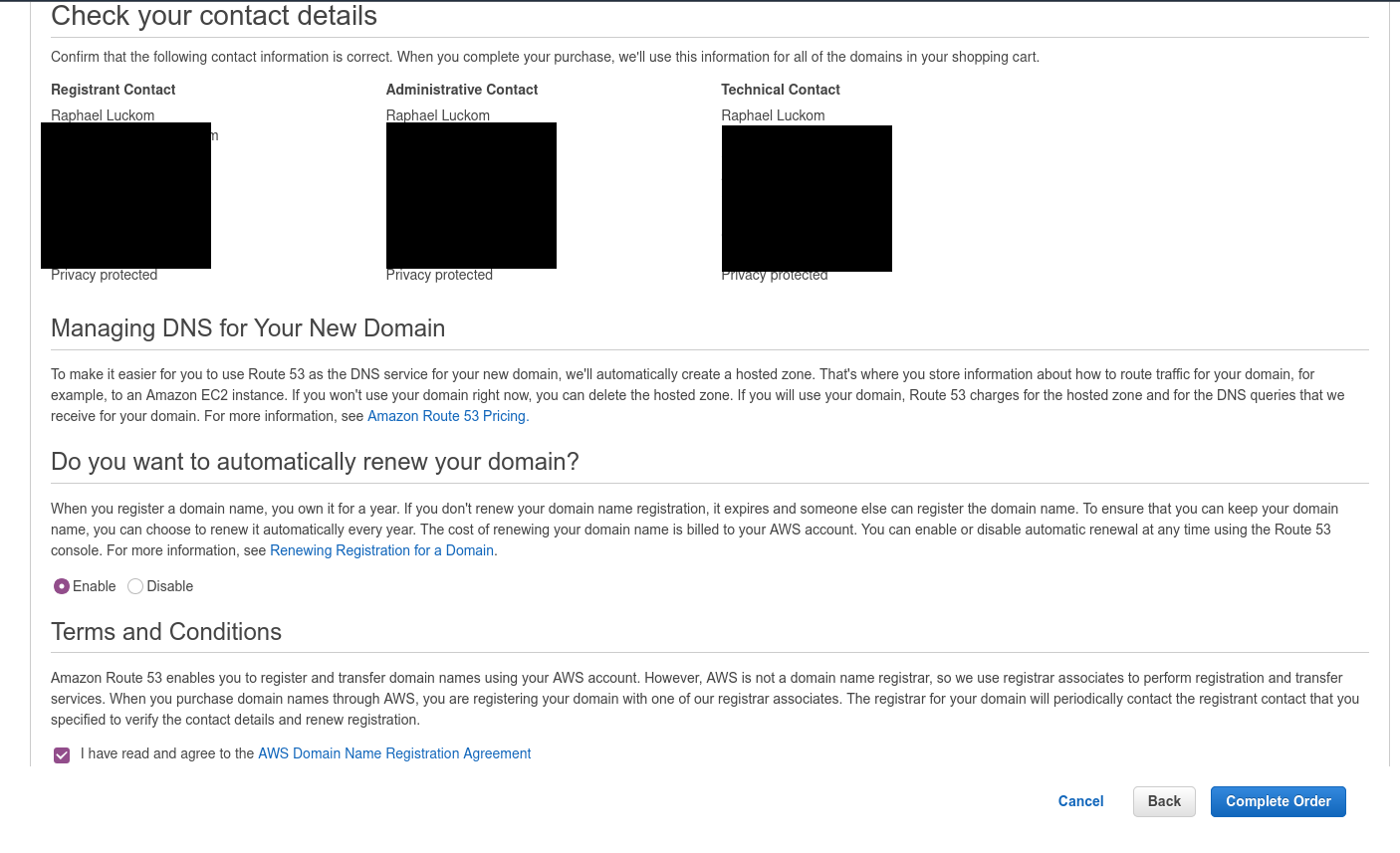

On the next page, you should see three blocks of contact information. Verify that the information is correct, and if you chose to enable domain privacy, verify that you see the words "Privacy Protected" at the bottom of each block of contact info. If everything looks good, choose whether you want the domain to auto-renew (probably a good idea, because if you forget to renew manually, someone else will be able to register the domain). Then click the checkbox accepting the terms and conditions and click "Complete Order"

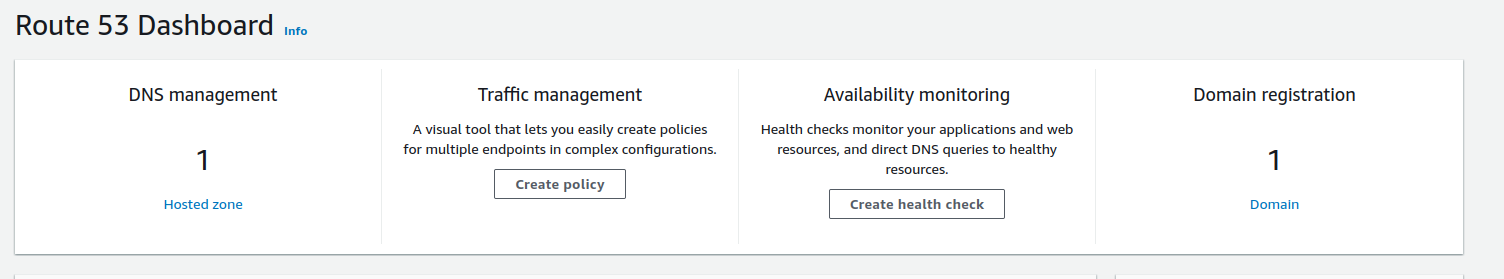

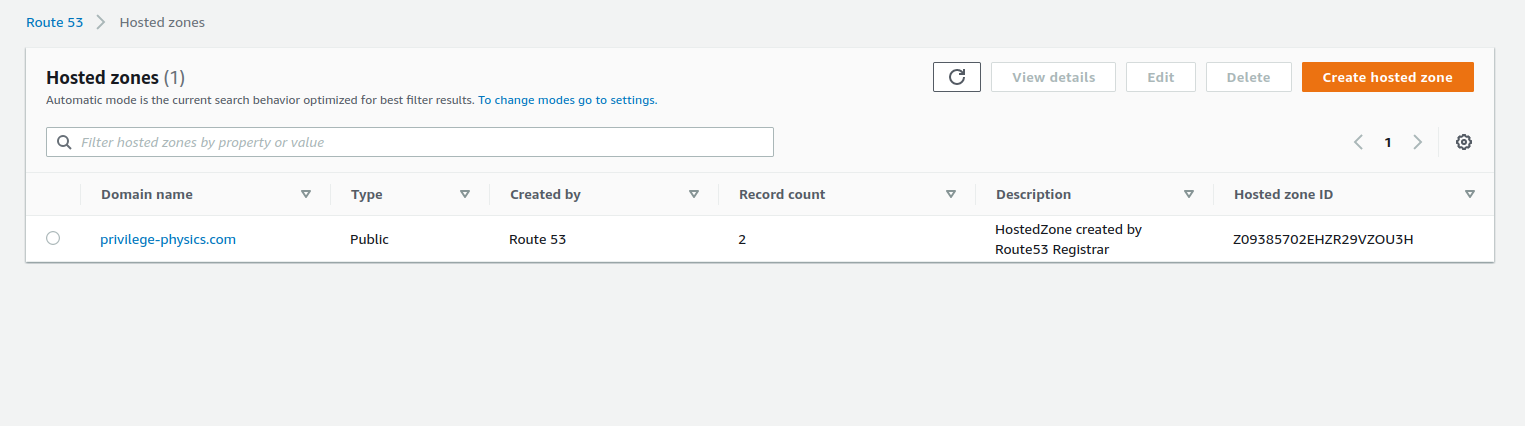

We don't have to do anything else today, but it's going to take up to three days for AWS to finish sorting things out behind the scenes so that we can use our domain. For the moment, the "Notifications" panel in the route53 console should show that your domain registration is in progress. You'll get an email when that process is complete, at which point you should also see that the route53 console shows that you have one Hosted Zone. When I registered a new domain to create these instructions, the registration process finished in about an hour and a half.

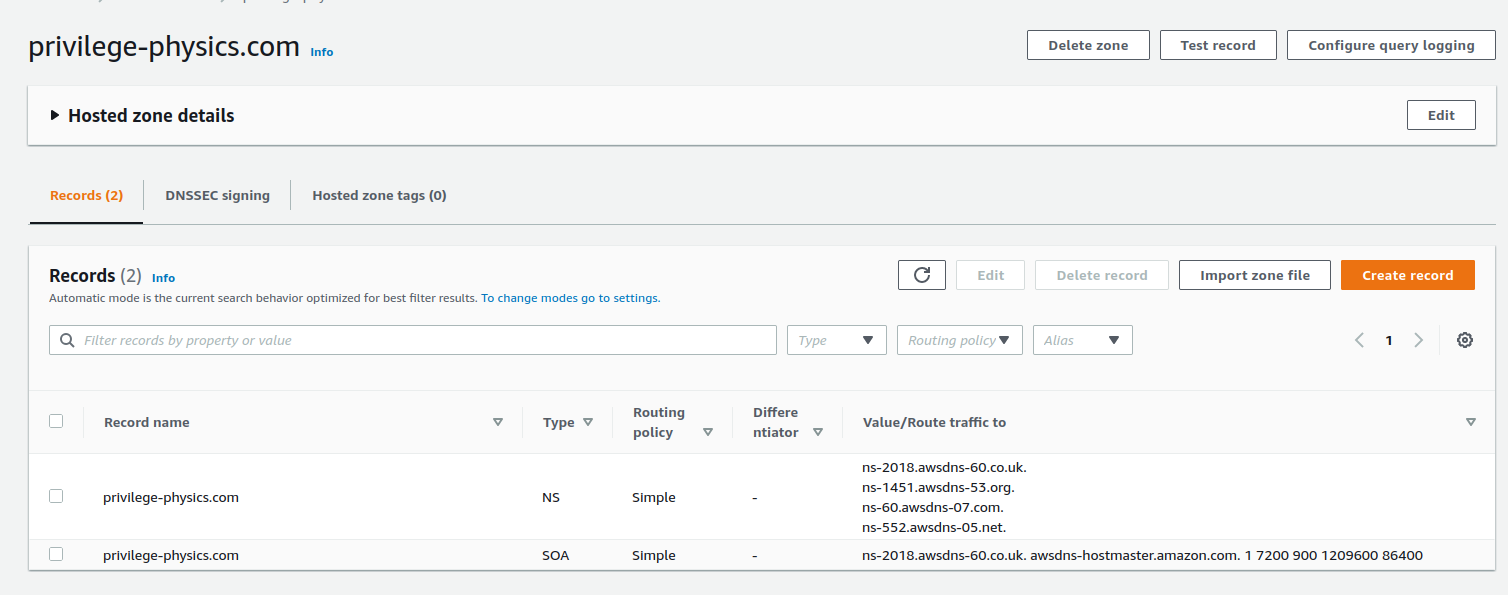

After the process is complete, when you look at your list of hosted zones (by clicking the link on the Route53 console) you'll probably see that your new zone has two records associated with it already. These are important-but-ignorable--they're plumbing that doesn't matter right now[6].

That's it for today--like I said, boring but necessary. This part of domain registration has to be a manual process, but for future exercises we'll be using terraform to configure the domain records, so we won't really be looking at this UI again.

Imagine you need something from a physical store you've never been to before. You get in the car, turn on whatever you use for navigation, and enter the name of the store. The app turns that name into a physical address and then gives you driving directions. Domain names are similar. Every computer connected to a network gets an IP address, which is a sequence of numbers like

172.0.0.1or8.8.8.8. An IP address is kind of like a physical address on the internet. A domain name is like what you type into a navigation app--it's a human-friendly name that the internet navigation system (DNS, for Domain Name System) can turn into an IP address that your browser knows how to find.Incidentally,

8.8.8.8is a good IP address to remember. It's a service Google operates and it's extremely stable. If you ever need to know whether an internet connection is working, typingping 8.8.8.8at the command line is a good way to find out). ↩︎Domain names are controlled by an organization called the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), a nonprofit group. But ICANN doesn't actually sell to consumers. Instead, different groups bid for control of top-level domains. Whoever wins gets the right to sell domains under that top-level domain--essentially, they're bidding on a monopoly on

.comdomains or whatever. There are some rules about how TLD operators are supposed to behave, but as in all human endeavors, expect shenanigans around the edges. Many of the weirder TLDs are basically rackets-- attempts to profit by forcing well-known companies to buy<theirname>.<weirddomain>at extortionate rates to block squatters. If you're considering one of the newer TLDs, I'd advise being especially wary of "sales," which seem like a way for scammy top-level-domain vendors to use the "low introductory price" strategy to get you to reserve a domain that will increase in price in subsequent years.The best-known and currently-least-free-for-all-y TLDs in the US are

.com(company),.org(organization, generally nonprofit), and.net(truly, whatever). Any of these may be used for a personal site, costing around $12 / year. People have different opinions about which one is most appropriate; I think there's a limit to the usefulness of those conversations. ↩︎Other well-known registrars (companies that sell domain names) are gandi.net, namecheap.com, and hover.com. We're going to use AWS, because using the same vendor for the domain name as we do for the rest of our infrastructure gives us the most flexibility to never have to think about this again, which is really the main thing you want from a registrar. ↩︎

"Route53" is the name AWS uses for its registrar and some other networky products. It's named after a highway in California. ↩︎

I have mixed feelings about this. It's quite similar to the way real estate transactions work, at least in the US--when you buy a piece of property, your information is recorded in the registry of deeds, where anyone can see it. This seems to me like a good thing--it should not be a secret who owns what land. Likewise, on the internet, there should be some mechanism for transparency about who is responsible for the content posted on a domain. On the other hand, it makes perfect sense to want to limit the places where one's personal information is published. Most TLDs, including

.org,.comand.netallow individuals to use domain privacy. When you use domain privacy, the registrar publishes its own contact information instead of yours, and if anyone wants to get your information, they have to ask the registrar directly and have a good reason for needing it. ↩︎You should see an NS record and an SOA record. The SOA record includes technical administrative information about how your domain name is configured. The NS record lists the name servers that officially say where requests for your domain should go. These are set-and-forget values for me. ↩︎