I’m sitting at my favorite spot on the end of the couch. Two air conditioners are running in different rooms, making an awful racket. Outside the window is an oak tree, leaves responding to every tiny movement in the air. In a gap between the leaves I can see a small bird on a branch, maybe a sparrow, silhouetted against the sky. I am not doing much of anything, but this moment is precious to me. I am letting my personhood— the feelings and impressions of my body and mind — be enough.

Personhood, in the sense that I mean, can’t be separated from a specific person, and it is different for each person. It exists only in moments of attention, when you recognize and encounter a mind — your own or someone else’s. An archaeologist who digs up a small pot sherd may encounter the personhood of someone who lived millennia ago. A garbage collector may encounter personhood in the trash from a party, if they observe what’s there and let it unroll into a story in their mind. There is no difference of degree between the personhood of a rich person or a poor person, a holy person or a profane person, an artist or an artless person. I use personhood instead of humanity because, while I am most interested in humans, the idea can be generalized to non-humans. When you see chewed toys near a dog’s bed, or a tree leaning out over a lake to catch more sunlight, you can similarly encounter a mind or motive force, more limited in its ability to communicate itself to you, perhaps, but not fundamentally different.

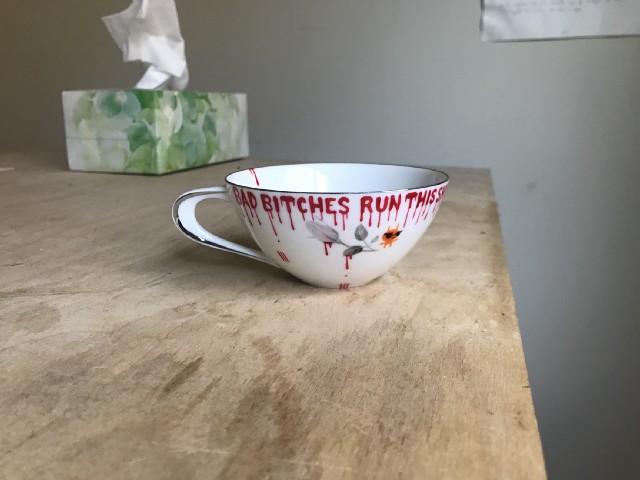

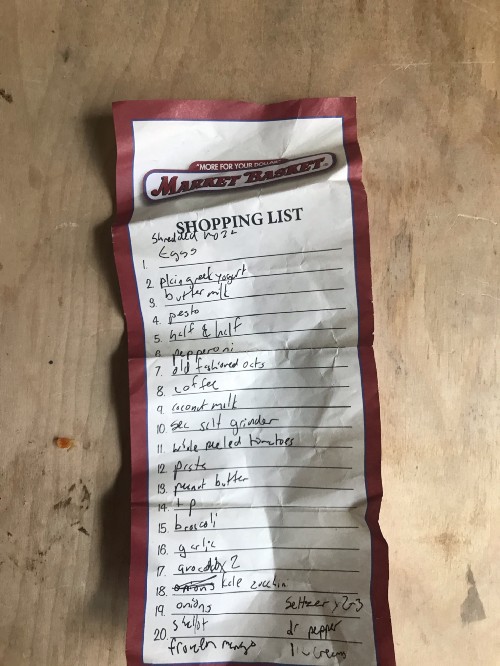

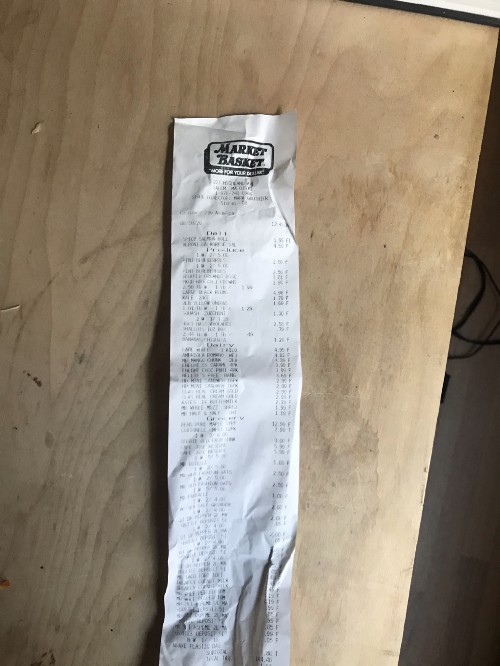

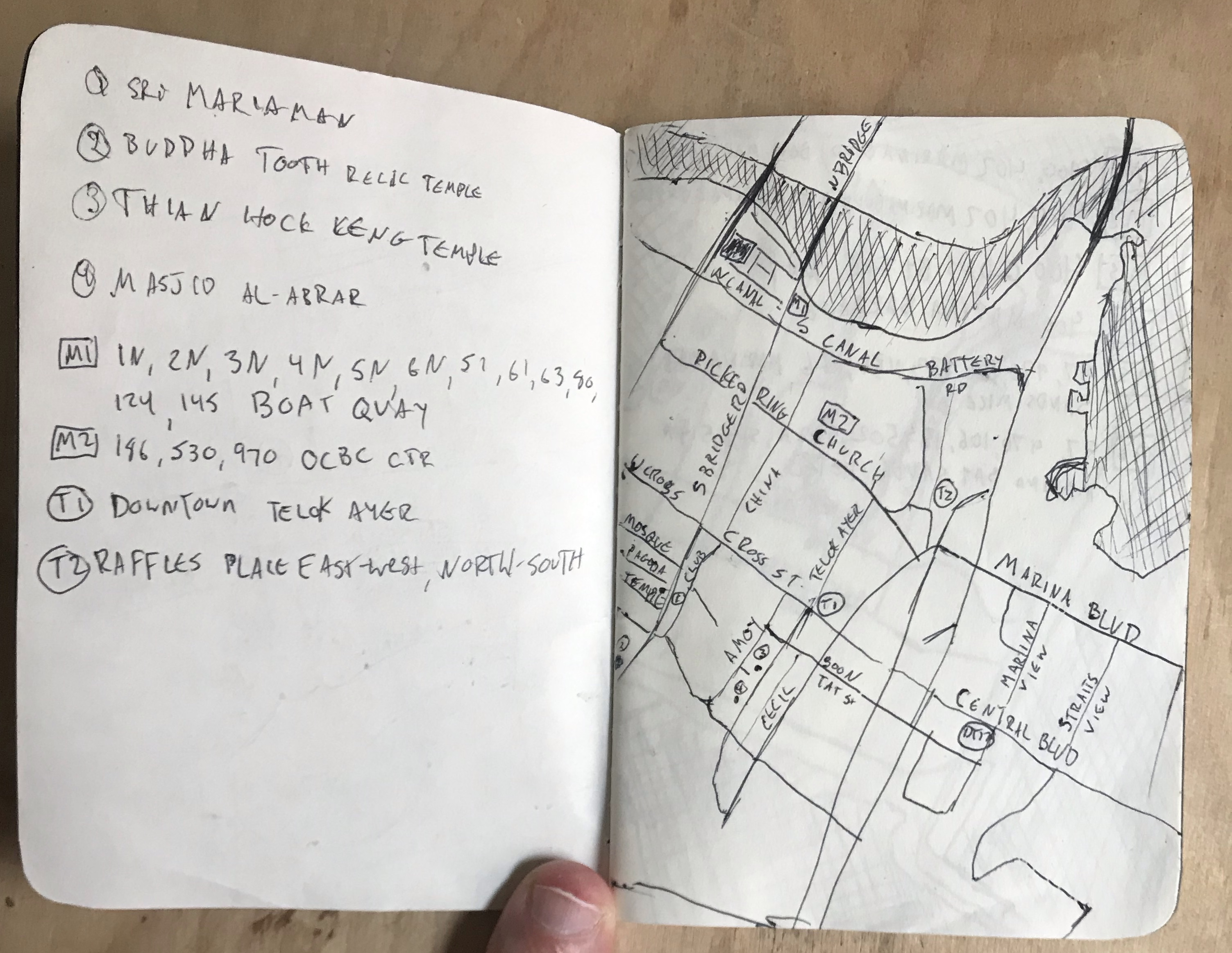

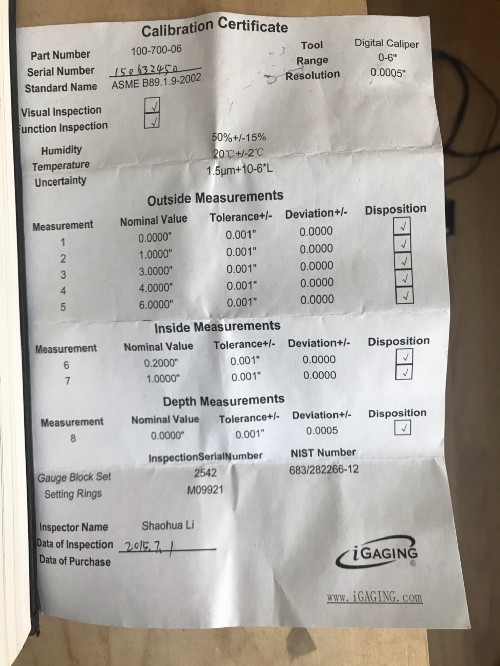

Certain objects project personhood more powerfully than others, especially in the context of our industrialized environment. The following pairs of images are of things I had around my home.

To me, the objects pictured on the right-hand side are more inviting, more comforting, and, in some ill-defined way, more valuable than the objects pictured on the left-hand side. Each object on the right bears an immediate connection to a specific person, while the objects on the left, though they are each highly advanced technological artifacts, tend to downplay or erase the role that humans had in their creation. The marks left by humans on the objects on the right give them a kind of range — a moment of human attention can utterly transform an object — while the technical virtuosity of the items on the left are simply the output of precise but narrowly limited industrial processes.

If you accept the premise that a moment of human attention can utterly transform an object (and especially the emotional response that people have to the object), and if you also accept the premise that personhood belongs equally to all living people regardless of any difference in circumstance, then you might also agree that as a society, we deliberately use a huge amount of human attention in processes that are intended to remove every trace of personhood from their final products.

When I quit my job a few weeks ago, my immediate goal was to slow down, take stock of the first 34 years of my life, and try to figure out what the best next step for me was. After the past weeks, I’ve identified this concept of “personhood in material culture” as the through line of my various interests. I intend to study something that I am for now calling “assertional making” — that is, ways of making that deliberately include the identity of the maker in the product, and honor their personhood. I am especially interested in identifying types of assertional making that can compete economically with existing low-wage jobs, and ways of promoting the value of “assertional goods” and giving assertional makers frictionless and rent-free access to markets.

If you’re interested in following along, I’ll be continuing to report here. If you’d like to contribute, then I have to admit that I’m not very good at getting a message out, so I would find it exciting and useful if you would let me know what you think, ask questions, and show this work to anyone you think might be interested.